Battle of Cheriton

By the winter of 1643, the English Civil War had been raging for over a year, right across the country. Parliament had control of London, East Anglia and the south-east. After a succession of victories in the summer of 1643 under Lord R Hopton, the royalists had driven the parliamentarians out of Somerset, Dorset and Wiltshire.

Hampshire was now in the front-line with the county hotly disputed by both sides. Parliament held Portsmouth, Southampton and Farnham. The royalists has captured Winchester and Andover and maintained a strong garrison at Basing House. Advanced posts were established at Alton, Petersfield and Arundel Castle.

In December 1643, the parliamentarian commander, Sir William Waller, launched surprise attacks to capture royalist troops at Alton and stormed Arundel castle. An uneasy truce settled over the county.

The grand royalist strategy for the 1644 campaigning season involved a three-pronged advance on London to end the war. Armies would descend from the north, along the Thames valley in the centre and from Winchester in the south. Parliament would be stretched to halt them.

To achieve this task, Hopton brought troops from the West Country and raised more men locally around Hampshire. Re-enforced by a contingent of the King’s main Oxford army under the aging Lord Forth, the army numbered around 3,500 infantry and 3,000 cavalry. Waller’s parliamentarian army comprised his West Country regiments, troops from the southern association of counties and the London Brigade. Just before the battle he also received a re-enforcement of cavalry troopers from the army of the Earl of Essex. Waller now had around 5,000 infantry and 4,500 cavalry under his command.

March 1644 saw both armies manoeuvring across the countryside as the weather leared. After three weeks of marching and counter-marching, Hopton’s royalists arrived in Alresford just ahead of Waller’s advanced guard. Skirmishing continued throughout the next two days, ending with a large royalist force under Sir George Lisle camped on East Down. Waller’s parliamentarians camped across the valley at Hinton Ampner. The die was cast for an epic showdown.

Images courtesy of Tillier’s Regiment of the Sealed Knot

Battle Location

The battle location has been the cause of controversy with historians for many years. Detailed analysis of first-hand accounts indicated where the armies started. There is also evidence of the use of key features such as Cheriton Wood and the Lanes. Above that, the exact area ha never been defined. Certainly the royalists advanced eastwards from Tichbourne Down. Apple Down is the next significant ridge , important to seventeenth century generals. Waller and his parliamentarians were camped overnight at Hinton Ampner, along the line of the current A272. As the two armies closed to contact, initial action in Cheriton Wood became general across four square miles of the downs. Finally driven from the field, the royalists retired to Basing House outside Basingstoke. One of the objectives of this project is to finally determine the exact location of the main fighting, using achaeological evidence.

The Battle of Cheriton

The royalist troops on East Down heard movement and noise throughout the night of 28th March. Thinking that Waller was about to retreat, they prepared to pursue the parliamentarians in the morning. Instead, as dawn rose on a misty morning, they were surprised to see over a thousand parliamentarian musketeers had taken possession of Cheriton Wood. Far from retreating, Waller was ready to fight. Around 7,000 royalists would take on 10,000 parliamentarians. By now, the Royalists had advanced from Tichbourne Down to Appledown. The parliamentarian army had drawn up in front of Hinter Ampner house, probably along the line of the modern A272.

Realising the threat posed to his left flank by the troops in the wood, Hopton detached a thousand musketeers of his own to re-take it. After receiving heavy musket fire, with the aid of a flank attack, the royalist swept forward with muskets clubbed, driving the parliamentarian before them. The in-experience London Brigade musketeers routed sweeping their supporting cavalry and artillery with them. Cheriton Wood was now firmly in royalist hands. As the rest of the army moved forward onto East Down, Hopton was well satisfied that all was going well.

Lord Forth was happy to remain on the ridge, allowing the parliamentarians to attack uphill and at great disadvantage if they so wished. Unfortunately a rash royalist officer, Sir Henry Bard led his infantry forward off the ridge to attack the parliamentarian. Disorientated in the smoke of battle, his regiment was surprised by parliamentarian cavalry and hacked to pieces. Seeing their perilous position, Forth felt obliged to support them, advancing his troops

piece-meal and yielding his position of advantage.

The parliamentarian musketeers advanced and fierce fighting broke out all along the line. From hedgerow to hedgerow, wall to wall the smoke hung heavy and the sound of clashing steel echoed across the valley. With numbers telling and heavily pressured, the royalist infantry was gradually forced backwards.

In desperation the royalist cavalry, patiently sitting on the ridge, was to be he least roll of the dice. With the only way to engage the enemy down the two lanes, the cavalry advanced in small troops. The parliament troopers were waiting for them, deployed and ready. The fight was pretty uneven. Outnumbered and hampered by the terrain, successive regiments were beaten back. The lanes ran with blood.

With the initiative firmly with the parliamentarians, Waller determined to make his numbers tell. Looping round the flanks on both sides, his infantry advanced relentlessly. All along the line, royalist infantry contested every yard of ground, but were forced back. Finally by late afternoon, they were back in their original positions, though sorely depleted in numbers.

Realising the day was lost Hopton sent off his artillery and baggage in good order. A lull in the fighting, sheer exhaustion probably, enabled the royalist infantry to leave the field, covered by a rearguard of cavalry.

The royalists retreated to Basing House, pursued by the victorious parliamentarians. Alresford was set on fire to cover the retreat. Despite being in combat for over eight hours, the royalists made Basing that night largely unhindered.

The field was left to the victorious parliamentarians. Considering the ferocity and length of the battle the casualties were fairly light. Around 300 royalists were killed, including the King’s cousin and several senior officers. Sir Henry Bard lost an arm and was taken prisoner. Parliamentarian losses were

reported as being around 60. This is clearly far too low but a good example of seventeenth century propaganda.

The battle was over, Waller was victorious and the southern pincer of the royalist strategy was destroyed. From now on, the royalist strategy would be defensive only, all designs on taking London dismissed as impossible now.

Scrubbs Farm

The Farm has been well surveyed over a long period of time with a wealth of information being available once it is collated. There is some debate as to exactly where the fighting took place, but the bare facts are not in dispute.

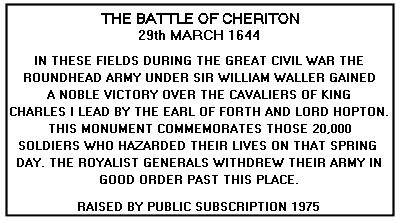

On 29th March 1644 the Battle of Cheriton was fought between 6,000 Royalists under Lord Hopton and the Earl of Forth and 10,000 Parliamentarians under General Waller. The result was an end to the Royalist advance in the south east, forcing Hopton to retire to Reading. It was the turning point in the war, being the first decisive victory for the Parliamentarians. Some 2,000 men were killed, with others being taken prisoner. A modern memorial stone can be seen at the junction betweens Scrubbs Lane and Cheriton Lane.

The Inscription reads: